Most woodworkers have an Achilles' heel in their woodworking skills. You wouldn't believe how many people have trouble with finishing, or with cutting simple joinery. Or design.

For me, for years, it was hardware installation.

Now I know that it sounds pretty cut and dried - lay it out, drill some holes, install a hinge, or a lid support, or whatever. But - being a perfectionist, it isn't always that simple. One pre-drilled hole placed ever so slightly off its mark can screw up everything. It can pull a lid off to one side, make a door hang crooked, or worse. All you do is increase your headaches.

With that in mind, I cut this box apart, separating the lid from the bottom.

Still, once the planing was done, it looked pretty impressive.

The only (slight) problem was that the lock was only 3/4" wide, while the box side was a little thicker, and I didn't like the look of that gap along the back. More on that later.

When you have an many people using your tools as I do, things are bound to get misplaced. So when I went to use the plunge router, the depth adjustment rod was missing. I swear, I heard it fall when I was picking up the router. But I never could find it. And I was tired of wasting time looking for it, so I did the next best thing - I used a pencil.

This is woodworking-on-the-fly, no doubt.

(The blue tape is holding down a little edge that was chipping off - I simply glued it down.)

not. any. more.

I kick ass on hardware.

As John Eugster likes to say - dutchmans are his friends. So I pieced in a small piece of wood behind the lock to fill in that gap. If I hadn't just told you about it, you wouldn't even know it is there.

And that is what we call expertise, baby!

I can make one holy-hell-of-a-mess when achieving that level, though. My shop looked like a bomb went off in it by the time I was finished.

Yes, that is a little smear of blood on the front of the chest. That was a very sharp chisel I was using. (Thanks, Eric, for sharpening everything!)

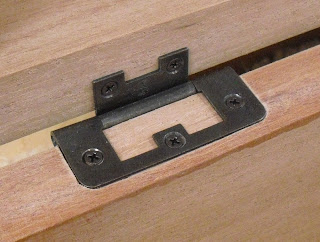

The last step was installing the hinges, and even though they are no-mortise hinges, they were a little too thick to use without setting them in a mortise. So I screwed them into place,

At least not anymore.

Next step - making some interior boxes to hold the cremains, and apply a finish. Stay tuned...

Oh, by the way - I did a little math, trying to figure out how many hours I've put into woodworking. I think a very conservative guess for the number of hours a week I've put in over the years is twenty. For many years I put in three times that but for some - I did nothing at all. So twenty seems a fair estimate.

Twenty hours a week, at fifty weeks per year is a thousand hours. And I've been doing this steadily for forty odd years.

40,000 hours? Are you kidding me?